by Stephen Griffin

Ireland has a strong tradition of families who entered military service abroad, whether in France, Austria, Spain or elsewhere.[1] Of particular interest in Austria were families such as Taaffe of Sligo, Wallis of Dublin, O’Dwyer of Tipperary, Laval Nugent of Westmeath and O’Kelly of Galway.[2] It is worth noting that Limerick also possesses a strong connection with the Irish diaspora in Austria via first and second-generation members of the Browne and Lacy families. The Brownes of Camas played prominent roles in the expansion, consolidation and defence of the Austrian Habsburg monarchy throughout the long eighteenth century, and it was through the activities of General George Browne of Camas that the family came to be established in Central Europe.

George Browne was born in the mid-seventeenth century [c.1660], the son of John Browne of Camas, Limerick, and Mary Roe of Hackettstown, Waterford. The eldest of eight siblings, Browne and his brother Ulysses entered the Jacobite army raised by Richard Talbot, Earl Tyrconnell in 1688. George Browne was a member of a regiment of 1,800 Irish soldiers that had been stationed in England and was detained and sent to Austria following the flight of James II into exile. Poorly equipped and ill disciplined, they were eventually dispersed into the regiments of the Hapsburg imperial army. Meanwhile, it is speculated that Ulysses Browne may have served in Mountcashel’s infantry which was dispatched to France in exchange for French troops to help the Jacobites fight William III in 1690. He presumably made his way to Habsburg Austria in the years after the Treaty of Limerick.[3]

During those years, the Habsburg monarchy was engaged in a war of reconquest (on its eastern borders). The failure of the Ottomans to capture Vienna in 1683 had led to a major resurgence of Habsburg power in Hungary and the Balkans as the emperor gained large swathes of territory which had been under Ottoman rule since the 1520s. This period also marked the emergence of one of Austria’s most famed soldiers: Prince Eugene of Savoy, whose crushing victory over the Ottomans at the battle of Zenta in 1699 ended the Great Turkish War.[4] As will be seen, Eugene would be influential in Browne’s career and held him in high esteem. Browne appears to have been with a company of Irishmen who were assigned to Franz Helfried, Graf Jörger’s Regiment in Belgrade in 1690. Regiments in the Imperial army were often bought and sold by officers who could afford to purchase them as Oberst-Inhabers (colonel-proprietors) and who then gave their names to the regiments. Browne appears as an officer of the same regiment at different times over the next fifteen years under different colonel-proprietors who succeeded Jörger including Laurent Victor, Graf Solari and Joseph Philipp, Graf Harrach.[5]

War erupted between Habsburg Austria and Bourbon France over the contested throne of Spain following the death of King Carlos II in 1700. Carlos’s sisters had married Louis XIV of France and Emperor Leopold I respectively. As the heavily disabled Carlos was unable to produce an heir, Europe was plummeted into conflict following his demise, as the Habsburg emperor and king of France each contested the right of their specific candidates for the Spanish throne.[6]

At this time, Browne was serving as an Obristwachtmeister (major) in Solari’s Regiment when Prince Eugene began campaigns against the French in Italy in 1701-2.[7] Following Eugene’s ascendancy to president of the Hofkriegsrat (Imperial War Council) in 1703, the prince attempted to remove the practice of buying and selling regiments and commissions, preferring instead to promote men who followed orders and displayed bravery in combat.[8] It was during this time that Eugene recommended George Browne for a full colonelcy in 1705. Browne’s brother, Ulysses, was also made colonel of the Hohenzollern Regiment in the same year, following a recommendation from John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough.[9] Still in Italy in 1707, George Browne was then wounded in a sortie at the siege of Milan when he was shot in the face by a musket ball.[10] He spent that year in command of the garrison of Susa in Piedmont. He was still on campaign in Italy the following year when a dispute arose regarding his pay. Prince Eugene next recommended Browne for the position of General Feldwachtmeister (equivalent to Major-General) and sought to procure him the official salary from the Hofkriegsrat. Eugene suggested that Browne be supplied with at least a colonel’s salary to be supplemented by a captain’s wage, otherwise Browne could not be expected to serve.[11] The issue was resolved in September 1708.[12]

Attempts to bolster Habsburg forces in Spain and to open a new front in French territory in 1709 led to the creation of two new imperial regiments of 1,500 men each. In a letter from Prince Eugene in February 1710, Browne was informed that he would command one of these.[13] According to Eugene, Browne’s presence would allow the allies to make the most of the 3,000 new recruits and the diversionary attacks against France.[14] Browne landed in Tarragona in 1710 and served under Guido, Graf von Starhemberg. Following Starhemberg’s defeat at the battle of Villaviciosa in December 1710 and his subsequent retreat into Catalonia, Browne garrisoned the town of Balaguer in 1711. Bourbon Franco-Spanish forces almost cut Browne off from Starhemberg’s column when, on 23 February, Browne learned of their approach and had the fortifications destroyed and his cannons dumped into the River Segre before retreating.[15] The allied defeat at Villaviciosa dashed any Habsburg hopes for a victory in Spain and although the war continued on, it was clear that the Bourbons now held supremacy.[16] It was now suggested that Browne’s regiment be reduced and its officers returned to Austria and Hungary where the regiment could then be repopulated with companies already serving in Hungary.[17]

Furthermore, the death of Emperor Joseph I in April 1711 led to the return of Archduke Charles – the Austrian candidate for the Spanish throne – to Vienna to succeed his brother as Emperor Charles VI. The succession of Charles would mark the beginning of the final chapter of the War of the Spanish Succession. Unwilling to allow Charles to possess the contested Spanish dominions in addition to his inheritance in Central Europe, Britain, France, Spain and the Dutch made peace in 1713 and Charles’s rival – Philip duc d’Anjou was formally recognised as Philip V of Spain. The emperor begrudgingly accepted peace the following year.[18]

At the war’s conclusion, Browne was made colonel-proprietor of a regiment of infantry in the Imperial army. The role of lieutenant colonel was granted to his brother-in-law, Patrick O’Neillan, who came from Dysert O’Dea in County Clare.[19] Browne’s brother, Ulysses, virtually retired from the army and settled in Frankfurt. However, the latter’s son, Maximilian Ulysses von Browne, had been born in Basel, Switzerland in 1705 and had been sent back to Limerick to be educated at a Protestant diocesan school. The young Maximilian then returned to Austria in 1715 and gained a commission in his uncle’s regiment.[20]

An alliance between the emperor and Venice in 1716 led to the outbreak of the Austro-Turkish War of 1716-18. When Prince Eugene besieged Temesvár (modern Timişoara in Romania) in autumn 1716, Browne was the one to gain a foothold inside the ‘Grosse Palanka’, a wooden palisade which defended the city’s suburbs. Once this was taken, Eugene was then able to advance further towards the city, which surrendered in October.[21] After the attack on the palanka Browne was reported wounded.[22] The following year, in June 1717, the imperial army besieged Belgrade. It was during this siege, and as an Ottoman relief column approached, that Eugene managed to avoid being surrounded on both sides in the battle of Belgrade in August 1717. As the prince had to fight on both sides, Browne remained in command of troops who remained in the trenches and in the city’s suburbs to guard against Ottomans attacks from inside the city.[23]

During the Austro-Turkish War Browne also wrote the ‘Kriegs Exercitum’, which still survives in the War Museum in Vienna. As commanding officers in the Imperial army were expected to draft their own drills and codes of conduct for their regiments (there were no general regulations), Browne wrote his instructions, and they are described by Christopher Duffy as ‘one of the most complete descriptions we have of the organisation and appearance of an Austrian regiment of the time’.[24]

The Austro-Turkish War concluded with the Peace of Passarowitz in 1718. Browne had applied unsuccessfully for the command of the garrison at Ofen (now part of modern Budapest) but his regiment was ultimately stationed in Milan.[25] The regiment’s time on garrison duty in 1720s Lombardy was not without incident and there were accusations and an investigation against the regimental quartermaster regarding the misappropriation of regiment funds worth 12,200 florins.[26] Browne’s coterie of Irish officers could also find themselves at odds with and engaged in quarrels with their German counterparts.[27] These stories are also recounted by Duffy in his biography of Browne’s nephew Maximilian.[28]

The many innumerable Irish families who migrated throughout continental Europe in the eighteenth century often sought access and inclusion to the ranks of the local nobility, which required a proven family pedigree.[29] In 1716, Browne and his brother, Ulysses, were issued with a patent of nobility from Emperor Charles VI. This was prepared by Baron William O’Kelly von Aughrim, an important figure in the intellectual world of eighteenth-century Vienna, who served as Supreme Herald of the Holy Roman Empire. The Brownes were also granted an estate in eastern Bohemia. In February 1725, they were granted a pedigree from the Ulster Herald of Arms which served as a Hanoverian acknowledgement of their pedigree in Ireland. As if to cover all bases, the brothers also obtained a Jacobite peerage from the Stuart court in exile in Rome, in April 1726.[30]

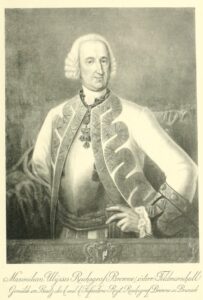

Browne’s last years were beset by illness and, as a precaution, he made his nephew, Maximilian, his sole heir.[31] Browne finally died in Pavia while on garrison duty with his regiment in 1729. Ulysses Browne died in September 1731 in Frankfurt. The full career of Browne’s nephew and Ulysses’s son, Maximilian, cannot be recounted here but a short overview will suffice. Promoted to major-general in 1735, the following year he was given command of his own regiment and would take a seat on the Hofkriegsrat in 1739.[32] Browne defended the monarchy under Empress Maria Theresa throughout the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48). He was forced to withdraw from Habsburg Silesia in the face of Frederick the Great of Prussia’s invasion in 1740 but took part in the invasions of Bavaria and of southern France. For his role in defending and consolidating the rule of Empress Maria Theresa, Browne was awarded the Austrian Order of the Golden Fleece. In peacetime he served as governor of Transylvania and of Bohemia, where he owned an estate.[33] Maximilian Browne died from his wounds at the Battle of Prague during the Seven Years’ War in June 1757. He was survived by his wife Maria Phillipina Magdalena von Martinitz, whom he had married in 1725, and his two sons, Phillip and Joseph. Philip died without heirs in 1803 following a career in the military and Joseph was killed in battle in 1758.[34]

Dr Stephen Griffin specialises in diplomacy, exile, and the early modern Irish diaspora in Europe. He currently works for Limerick Civic Trust and is working on his first book with Brepols.

[1] Harman Murtagh, ‘Irish soldiers abroad, 1600-1800’ in Thomas Bartlett and Keith Jeffery (eds) A military history of Ireland (Cambridge, 1997), pp 294-314.

[2] For an overview see, Declan Downey, ‘Wild Geese and the double-headed eagle: Irish integration in Austria c. 1630-1918’ in Paul Leifer and Eda Sagarra (eds) Austro-Irish links through the centuries (Vienna, 2002), pp 41-57.

[3] Christopher Duffy, The wild goose and the eagle: a life of Marshal von Browne, 1705-1757 (London, 1964), pp 1-6; James O’Neill, ‘Conflicting loyalties: Irish regiments in Imperial service, 1689-1710’, Irish. Sword, XVII (1987), p. 117.

[4] Michael Hochedlinger, Austria’s wars of emergence, 1683-1797 (New York, 2013), pp 153-66; Derek McKay, Prince Eugene of Savoy (London, 1977), pp. 13-29; 41-7.

[5] Alphons, Freiherr von Wrede (ed) Geschichte der k. und k. Wehrmacht: Die Regimenter, Corps, Branchen und Anstalten von 1618 bis Ende des XIX. Jahrhunderts (Vienna, 1898), p. 443, n. 1; O’Neill, ‘Irish regiments in Imperial service’, p. 117; Hochedlinger, Austria’s wars of emergence, pp 115-6.

[6] Hochedlinger, Austria’s wars of emergence, pp 174-6.

[7] Feldzüge des Prinzen Eugen (20 vols., Vienna, 1876-91), IV, pp 244; 257.

[8] McKay, Prince Eugene, pp 71; 227-8.

[9] Eugene to Hofkriegsrat [HKR], 5 Jun. 1705, ibid., VII, p. 169; Eugene to HKR, 6 Dec. 1705, ibid., VII, p. 510.

[10] Eugene to Joseph I, 3 Mar. 1707, ibid., IX, p. 42.

[11] Eugene to HKR, 22 Aug. 1708; Eugene to Harrach, 22 Aug. 1708; Eugene to HKR, 26 Sep. 1708, ibid., X pp 199-200; 249.

[12] Eugene to HKR, 3 Oct. 1708, ibid., X, p. 266.

[13] Eugene to Browne, 1 Feb. 1710, ibid., XII, p. 16.

[14] Eugene to Charles III, 21 May 1710, ibid., XII, p. 87.

[15] Feldzüge des Prinzen Eugen, XIII, pp 321-2 ; 345.

[16] Virgina Léon Sanz, Carlos VI: el emperador que no pudo ser rey de España (Madrid, 2003), p. 191.

[17] Eugene to Charles VI, 5 Nov. 1711, Feldzüge des Prinzen Eugen, XIII, pp 143-6.

[18] Henry Kamen, The war of succession in Spain, 1700-15 (London, 1969), pp 23-4; William O’Reilly, ‘Lost chances of the House of Habsburg’, Austrian History Yearbook, 40 (2009), p. 61.

[19] Von Wrede (ed) Geschichte der k. und k. Wehrmacht, pp 516-7; Luke McInerney, ‘The O’Neylons of Dysert and Austria’, The Other Clare, XLII (2018), pp 28-30.

[20] Duffy, Marshal von Browne, pp 7-8.

[21] Feldzüge des Prinzen Eugen, XVI, pp 253-5; Johann N. Preyer, Monographie der königlichen Freistadt Temesvár (Temesvár, 1853), p. 49. As a fortification, a palanka was typically used by the Ottomans throughout their Hungarian border. Burcu Özgüven, ‘The palanka: a characteristic building type of Ottoman fortification network in Hungary’ in Electronic Journal of Oriental Studies, IV (2001), pp 1-12.

[22] Eugene to HKR, 1 Oct. 1716, Feldzüge des Prinzen Eugen, XVI, p. 144.

[23] Hochedlinger, Austria’s wars of emergence, p. 195; Feldzüge des Prinzen Eugen, XVII, pp 130, 139.

[24] Duffy, Marshal von Browne, pp 8-12.

[25] Eugene to HKR, 3 Sep. 1717, Feldzüge des Prinzen Eugen, XVII, p. 157.

[26] HKR, July 1725; HKR, Sep. 1725 (Kriegsarchiv, Vienna, Hofkriegsrat, Expedit 573, fos 1164; 1573-4). HFK, Aug. 1725 (Kriegsarchiv, Vienna, Hofkriegsrat, Registratur 577, f. 788).

[27] HKR, Apr. 1727 (Kriegsarchiv, Vienna, Hofkriegsrat, Registratur 593, fos 483-4.

[28] Duffy, Marshal von Browne, p. 16.

[29] Mary Ann Lyons and Thomas O’Connor, From strangers to citizens: the Irish in Europe, 1600-1800 (Dublin, 2008), p. 140.

[30] Duffy, Marshal von Browne, pp 13-4; Downey, ‘Wild geese and the double-headed eagle’, p. 48; Melville Amadeus de Massue de Ruvigny, 9th Marquis of Ruvigny and Raineval, The Jacobite peerage, baronetage, knightage and grants of honour (London, 1904), pp 22-3.

[31] Duffy, Marshal von Browne, pp 18-9.

[32] Readers are advised to see Duffy, Marshal von Browne, for a full account of the life of Maximilian Ulysses von Browne. Also see, ‘Browne, Maximilian Ulysses, Reichsgraf von’ in Constant von Wurzbach (ed.), Biographische Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich (60 vols, Vienna, 1856-91), II, pp 161-4.

[33] Downey, ‘Wild geese and the double-headed eagle’, pp 49-51; ‘Browne, Maximilian Ulysses, Reichsgraf von’ p. 163.

[34] Duffy, Marshal von Browne, p. 260; ‘Browne, Maximilian Ulysses, Reichsgraf von’ pp 163-4.