by Seán William Gannon

Limerick’s Jewish community was established in the early 1880s when Lithuanian and Polish immigrants began arriving in the city to join the handful of co-religionists already resident there. The Limerick Hebrew Congregation (LHC) was formally established in late summer 1895 and, by 1901, this community had grown to around 170-strong. However, the decades thereafter were a time of decline as members left Limerick for personal, religious, or economic reasons. The LHC was left without a minister following the death of Rev. Simon Gewurtz in 1944 and its synagogue at 72 Wolfe Tone Street closed its doors three years later.[1] The building was sold in 1953, marking what the Jewish Chronicle called ‘the final chapter of an interesting community’.[2]

One of the central figures in the history of this ‘interesting community’ was its first minister, Rev. Elias Bere Levin. Born in Telz, Lithuania c.1863, he undertook religious studies in Telz, Zader, and Slonim and was ordained a rabbi aged only nineteen. He then briefly ministered in Vilna, earning a reputation as an expert sofer/scribe, before emigrating to Limerick with his wife, Annie, in 1882. Apart from a two-year sojourn in the United States in the mid-1890s, the Levins remained in Limerick until 1912, living at various addresses on and around Wolfe Tone Street (then called Collooney Street), ultimately at number 18. When Levin became minister to the LHC is unclear. According to the historian Louis Hyman, he ‘was authoritatively appointed Reader and shochet’ in 1886 and he was certainly officiating at weddings as early as 1890.[3] However, on the evidence of the occupations recorded on the birth records of his Limerick-born children (the Levins welcomed seventeen children between 1881 and 1910, fourteen of whom survived infancy), he did not become a full-time remunerated rabbi until his return from America having, as was commonplace amongst provincial ministers with small congregations in the UK, previously supplemented his income with other work – in his case as a credit draper.

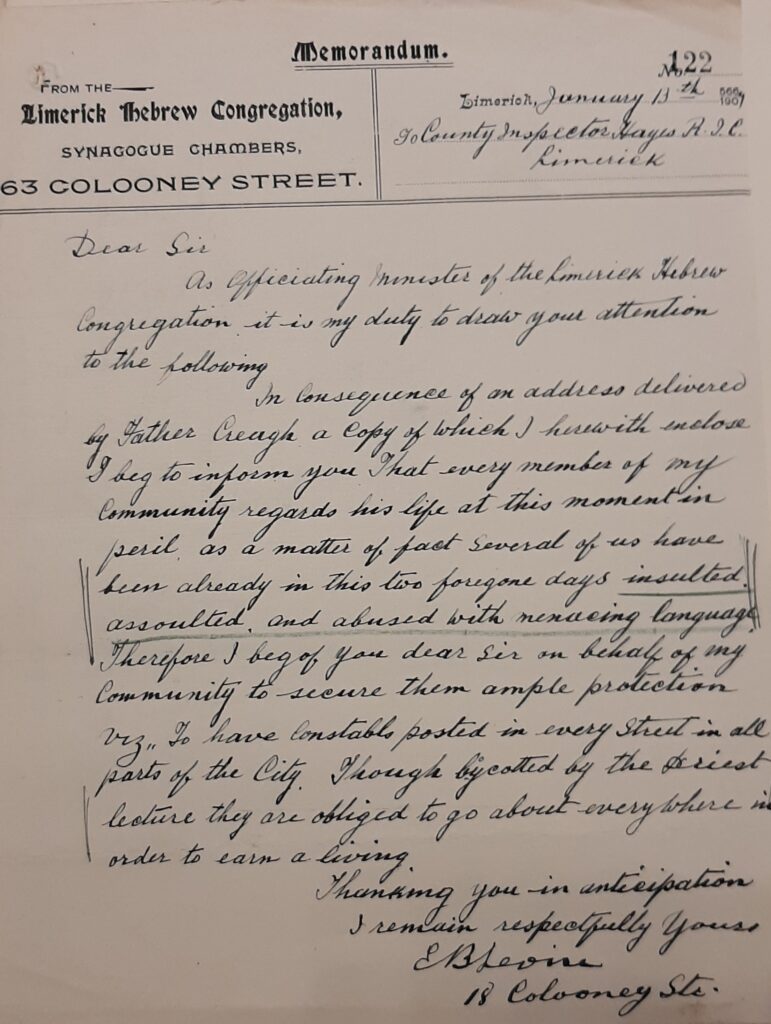

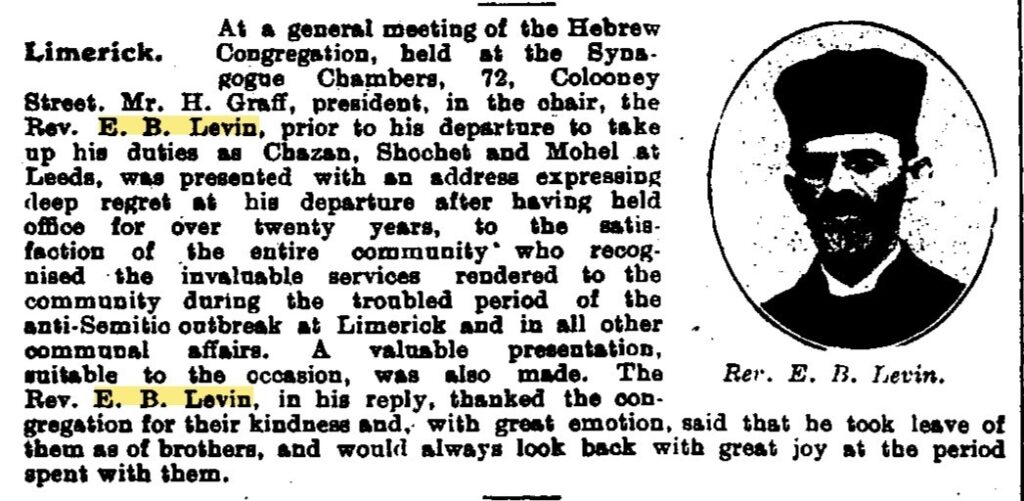

What is clear from extant archival sources is that Levin was a diligent pastor and an effective community leader. In a presented address to mark his departure from Limerick for Leeds in autumn 1912, the then president of the LHC, Hyman Graff, told him that ‘the entire community recognised the invaluable services he rendered … during the troubled period of the anti-Semitic outbreak at Limerick and in all other communal affairs’ for over twenty years.[4] This ‘anti-Semitic outbreak’ commenced in January 1904 when two virulently Judaeophobic sermons by a local Redemptorist, Fr John Creagh, gave rise to sporadic violence against Limerick’s Jews and a two-year economic boycott which forced several to leave. Levin certainly exaggerated the scope and scale of this Limerick Boycott, both in terms of its violence and economic impact – exaggerations which continue to shape the false ‘Limerick Pogrom’ narrative today. His overstatements in this respect were likely conditioned by his upbringing in mid-nineteenth-century Lithuania, where the desire to secure official protection saw Jewish communities occasionally overplay the antisemitic violence, or the threat thereof that they faced;[5] and Levin was determined to have his community defended, displaying what his obituarist Isaac Sieve (whose family lived on Collooney Street in 1904) described as ‘ability and courage of a high order’ to this end.[6] For example, he successfully petitioned the Royal Irish Constabulary county inspector for Limerick, Thomas Hayes, to afford his community ‘ample [police] protection’ in the wake of Creagh’s first sermon and he engaged the public support of respected Irish nationalist leaders such as John Redmond and Michael Davitt.[7] He also personally called to the Bishop’s Palace at Corbally to seek the intercession of Limerick’s Catholic bishop, Dr Edward O’Dwyer, albeit with little result. Most importantly, perhaps, in terms of his community’s welfare, he secured the assistance of the Jewish authorities in Dublin and London who raised the Limerick community’s plight with Irish political and ecclesiastical leaders and opened a fund for the relief of those suffering financial distress on account of the boycott.

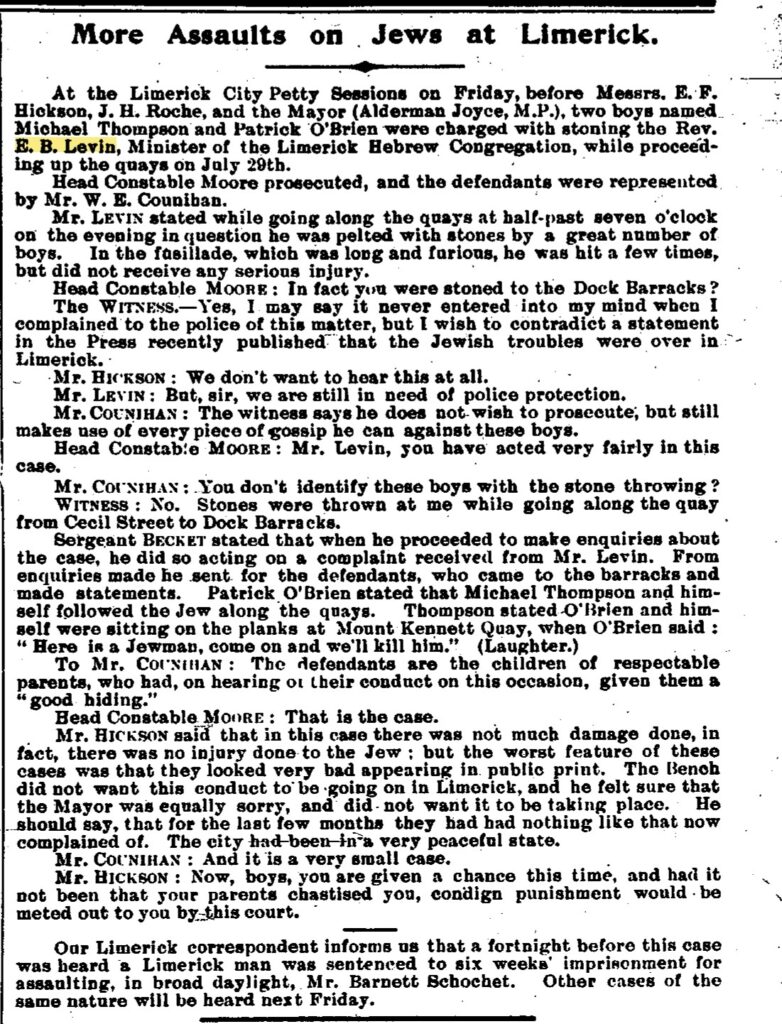

The Limerick Boycott was by no means the only occasion on which Levin rallied to his community’s defence. For example, he publicly rebutted concerns raised by Dr J.F. Shanahan of Limerick’s Rural Sanitary Board in September 1892 that the cholera then raging in Hamburg could be introduced into the city by local Jewish pedlar-drapers by means of personal transit or the importation of contaminated clothing through the port.[8] Levin also protested the verbal and physical abuses to which members of his community were intermittently subjected, and of which he was himself a target several times.[9] The ‘other communal affairs’ to which Graff referred included Levin’s strictly religious duties and the wider community work in which he took a proactive part. He established a Bikur Cholim Society for the relief of the sick in 1889 and was involved with the Limerick Hebrew Young Men’s Association (to which he regularly lectured on Jewish history) and the Limerick Hebrew Ladies’ Association, established in 1893 and 1894 respectively. He was also a prime mover in the establishment of both the Limerick Jewish Board of Guardians in 1901 and Holy Burial Society of the Limerick Hebrew Congregation one year later.

Hyman states that Levin was also instrumental in smoothing over the ‘petty altercations that disfigured communal life’ in the 1880s – internecine squabbles which, as the historian Natalie Wynn has observed, were commonplace in small purely immigrant communities like Limerick’s where personality clashes and competition for community status could get out of hand.[10] However his unifying days, which culminated in the establishment of a unitary LHC under his leadership in 1895, were relatively short-lived. For Levin strongly took sides in community quarrels, particularly where questions of Jewish law and tradition impinged. Most significantly, he was a central figure in an increasingly bitter argument that developed in 1899, crystallized around the funding of a dedicated community cemetery in Kilmurry, and culminated in a violent brawl in the LHC synagogue at 63 Collooney Street in August 1900.[11] Formal schism followed immediately thereafter; a breakaway faction opened a rival synagogue at number 72 in mid-January 1901, with Rev. Moses Velitskin as minister, while Levin, as minister of the original LHC, vigorously asserted its authority and led efforts to safeguard its rights. Although the pressures of the Limerick Boycott had forced reunion by 1905 with 72 Collooney Street as the sole synagogue, good relations between members of the opposing factions were never fully restored.

The reasons for which Levin left Limerick for Leeds in 1912 are unrecorded and little is known of his life thereafter. He briefly served as a rabbi and reader at the Old Central Synagogue, before assuming the positions of ‘second reader’ and shochet at the Great Synagogue on Belgrave Street and where, as in Vilna, he was soon acknowledged as a notable scribe. Levin ministered at the Great Synagogue until his death in spring 1936 when he was eulogised by his colleagues as ‘a congregational official who carried out his duties in a true spirit of devotion and love for the ideals of Jewish Tradition’.[12] The same may be said of his ministry in Limerick.

[1] Gewurtz, who had been appointed minister in 1931, is buried in the Jewish cemetery in Castletroy.

[2] Jewish Chronicle, 26 June 1953.

[3] Louis Hyman, The Jews of Ireland: from earliest times to the year 1910 (Shannon, 1972), p. 211.

[4] Jewish Chronicle, 30 Aug. 1912.

[5] See Darius Staliūnas, Enemies for a day: antisemitism and anti-Jewish violence in Lithuania under the Tsars (Budapest, 2015), pp 40–6, 106–25.

[6] Jewish Chronicle, 12 June 1936.

[7] Elias Levin to Thomas Hayes, 13 Jan. 1904 (National Archives of Ireland, Chief Secretary’s Office Registered Papers, 1905/ 23538.

[8] Limerick Chronicle, 3 Sept. 1892. According to Shanahan, it was ‘a well-established fact that the disease was brought into Hamburg by a certain class of emigrants [i.e., poor Russian Jews], of whom we have a regular colony’ in Limerick.

[9] For examples of violence against Levin, see Court of Petty Sessions Order Books for Limerick city, 30 Nov.1883, 10 Oct. 1888, 11 Mar. 1892; Limerick Leader, 15 Apr. 1904, 11 Aug. 1905.

[10] Hyman, The Jews of Ireland, p. 211; Natalie Wynn, Community, identity, conflict: the Jewish experience in Ireland, 1881–1914 (Oxford, 2024), pp 140-3.

[11] For the detail of this argument and schism see Des Ryan, ‘Jewish immigrants in Limerick: a divided community’ in David Lee (ed.), Remembering Limerick: historical essays celebrating the 800th anniversary of Limerick’s first charter granted in 1197 (Limerick, 1997), pp 166–74; Wynn, Community, identity, conflict, pp 126–33.

[12] Jewish Chronicle, 12 June 1936.