by Martin Sheehan

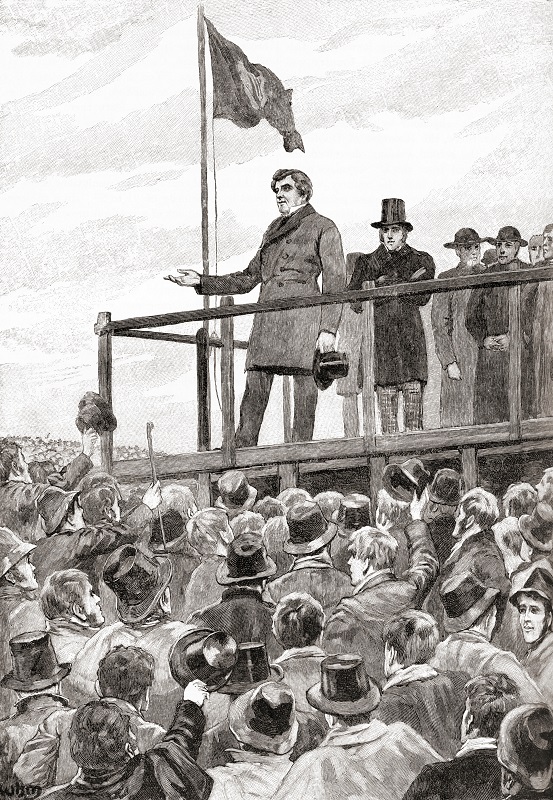

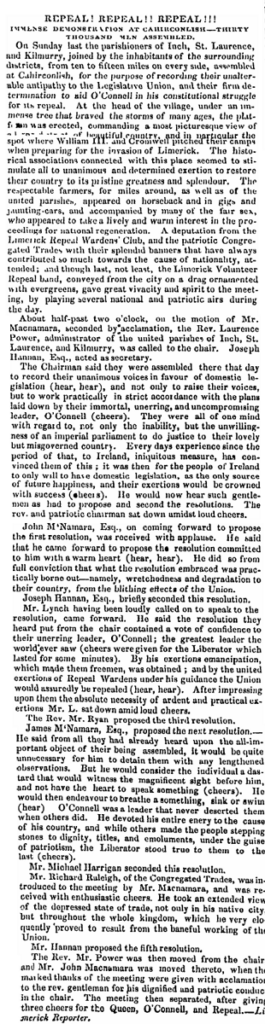

Limerick has led the way in many political innovations throughout history, most recently demonstrated by John Moran’s inauguration in 2024 as Ireland’s first-ever directly elected mayor. Not least, the city hosted the first of Daniel O’Connell’s monster Repeal meetings on 18 April 1843. According to the Limerick Reporter of 21 April, O’Connell led a procession of 250,000 people through the streets of Limerick, while the Nation put forward a more realistic figure of between 100,000 and 120,000 people.[1] Regardless of this discrepancy, it was still a massive crowd, and all the more remarkable in that only a few months previously O’Connell’s Repeal movement had lacked popular support. O’Connell was determined to repeal the 1801 Act of Union between Ireland and Britain and create a domestic Legislature in College Green, Dublin. The General Election of 1841 was a setback for O’Connell, and resulted in the decline of his political influence in parliament. Of 105 Irish members then elected to the House of Commons, O’Connell could only call on nineteen who declared themselves as Repealers, compared with forty-five in the election of 1832.[2]

The historian W.E.H. Lecky believed that it was the lack of Catholic clerical support for Repeal which contributed to the disappointing electoral results in the parliamentary elections of 1841.[3] The position of the Catholic clergy in Limerick on Repeal can be gauged from their absence from a Repeal meeting organised for a Church holiday on Thursday, 29 September 1842; only Rev. Maher C.C. of Abington, Murroe attended. In comparison, in 1837 every parish priest in Limerick city stood on a platform with O’Connell as he endorsed William Roche, a Liberal candidate, and David Roche, a Repealer, in that year’s general election.[4] The lack of enthusiasm by the clergy around the September 1842 meeting was recognised by the public and, in a letter to the Limerick Reporter published two days before, a Mr. Ryan of the North Strand pleaded; ‘let us hope, then, that all who profess to hold the principles of Repeal, will not decline to attend on this occasion, but generously press forward to the political temple (if I be allowed the expression) the place of meeting, and there contribute their mite on the altar of their country at the shrine of freedom.’[5] On the eve of the meeting Daniel O’Connell arrived in Limerick and was greeted by the St John’s Temperance Society Band and the mayor of Limerick, Martin Honan, who, according to the Limerick Chronicle, apprised him of the planned meeting. However, much to the surprise and disappointment of the organisers, O‘Connell left for Dublin the following morning. The paper commented that the meeting ‘commenced in the absence of all those respectable and influential persons who heretofore attended public meetings, and who were known to participate in the interest of every public question but this. [6]

O’Connell had been elected lord mayor of Dublin in October 1841 and, acknowledging the impartial nature of his mayoral duties, avoided overt Repeal agitation.[7] However, in the autumn of 1842, with the term of his mayoral office coming to a close, O’Connell directed his close confidantes Thomas Steele, Thomas Ray, William Joseph O’Neill Daunt and his son, John O’Connell, to undertake a provincial tour of the country to promote the cause of Repeal. O’Connell wrote to O’Neill Daunt ahead of the Repeal campaign, warning him to proceed cautiously and ‘to have the approval of the Catholic clergy in every place you move to’.[8] In Limerick, O’Connell looked to Rev. Thomas Coll (known as Dean Coll), parish priest of Newcastle.

Throughout 1842, the Repeal movement seemed to stall, The Times of London gloated ‘that the game is up for the old man’ (i.e. Daniel O’Connell), and both Prime Minister Robert Peel and the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Thomas de Grey, believed Repeal was no longer a serious threat.[9] Dean Coll, a noted orator, had been a prominent supporter of O’Connell following his success in a by-election Clare in 1828. He was rewarded for his contribution by an appointment as chaplain to the Order of Liberators, an association established by O’Connell to recognise those who had contributed to the cause of Catholic Emancipation. Coll, however, was not a supporter of Repeal and, in the parliamentary elections of 1832, supported two Liberal candidates against O’Connell’s Repeal nominees. He was also a keen supporter of William Smith O’Brien, a Liberal MP for Limerick, who had publicly asserted his independence from O’Connell.[10]

However, on Tuesday 13 December 1842 Coll chaired a meeting to organise a public dinner in Newcastle in honour of O’Connell on his return journey to Dublin, following his festive break at his home in Derrynane, County Kerry.[11] An invitation was sent to O’Connell by the secretary of the meeting, Michael Leahy, solicitor, which promised that, on this occasion, the Catholic clergy of the entire district would lead their parishioners in a procession to greet O’Connell on his arrival. This intervention by Dean Coll was probably due to the success of a previous Repeal meeting held in Bruff the previous month (in which the two curates of that parish had played a prominent role), and to a personal appeal by O’Connell to Coll. O’Connell claimed that he had met with Coll and had persuaded him on the practicality of Repeal; this in all probability occurred on 24 November 1842, when O’Connell passed through Limerick on his way to Kerry for his Christmas break.[12]

Dean Coll admitted that he had his doubts about the practicalities of Repeal, but said that he was persuaded by the growing support for the movement and the ‘gigantic intellect’ of O’Connell.[13] The Times claimed that at least twenty Catholic priests attended O’Connell’s tribute dinner at Newcastle.[14] The dinner itself was preceded by a Repeal demonstration which the Limerick Reporter estimated attracted a crowd, to number ‘at least fifty thousand persons.’[15] Coll’s standing within Limerick city and county made him an essential ally for O’Connell in providing Repeal with a justifiable and practical cloak of respectability. The Newcastle demonstration was important to O’Connell because it not only attracted national attention, but also tied the Catholic clergy in Limerick to the Repeal cause. O’Connell was delighted with the reception he received and, especially, Dean Coll’s endorsement. He remarked: ‘Oh how it delights me to-night to witness my beloved friend giving the sanction of his high authority and of his exalted station to my exertions.’ He announced that he was determined that this year would be known as the Repeal year. He also declared that ‘this is the first day of my new career.’[16] Following the successful meeting in Newcastle, Repeal meetings were organised in parishes across the county, culminating in the first of O’Connell’s ‘Monster Repeal Meetings’ in Limerick on 18 April 1843.

Martin Sheehan is a PhD student at the Department of History, Mary Immaculate College, Limerick. His research focuses on the growing political influence of the Catholic Church in the decades before the Great Famine, and how the Catholic Church came through this national catastrophe to establish a far stronger position in Irish life.

[1] Limerick Reporter, 21 April 1843; Nation, 22 April 1843.

[2] Paul Bew, Ireland: the politics of enmity 1789-2006, (Oxford, 2007), p. 153.

[3] W.E.H. Lecky, The leaders of public opinion in Ireland: Swift, Flood, Grattan, O’Connell, (London, 1871), p. 230.

[4] Limerick Star, 21 July 1837.

[5] Limerick Reporter, 27 September 1842.

[6] Limerick Chronicle, 1 October 1842.

[7] Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh, Ireland before the Famine 1798-1848, (Dublin, 1972), p.185.

[8] Maurice O’Connell, The correspondence of Daniel O’Connell vol. VII, (Dublin, 1978), p. 173.

[9] The Times, 28 March 1842, cited in Donal A. Kerr, Peel, priests and politics: Sir Robert Peel’s administration and the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland, 1841-46 (Oxford, 1984), p. 80.

[10] Limerick Chronicle, 14 January 1837.

[11] Limerick Reporter, 13 December 1842.

[12] Limerick Reporter, 25 November 1842, 10 February 1843.

[13] Limerick Reporter, 20 January 1843.

[14] The Times, 23 January 1843.

[15] Limerick Reporter, 20 January 1843.

[16] Ibid.