by Ed O’Shaughnessy

With the recent arrival in Canada of the iconic bronze shoe sculptures, considerable attention is being given to the Famine Exodus from Ireland to British North America. These sculptures – thirty pairs of bronze shoes – were placed at intervals along the National Famine Way, an interpretive trail marking the 165km march to Dublin of almost 1,500 evictees from the Strokestown estate in Roscommon for transport via Liverpool to Canada. Until recently, this Famine Way ended at the Dublin quays. But the Strokestown emigrants, who are commemorated by this trail, had not yet boarded a ship. In May 2024, the commemorative trail was extended to Canada, inaugurating the Global Irish Famine Way. With this extension, the story of the Famine Exodus, be it that of the “missing 1490”, or any of the hundreds of thousands of famine decade emigrants, can be more fully understood, and commemorated.

Limerick, with its advantageously placed commercial port, was a significant facilitator of the Famine Exodus, sending thousands to British North America, and especially to Quebec. The scale of the exodus to British North America is appreciated with the declaration that 15 percent of Canada’s population claims Irish ancestry. For those wishing to emigrate from western Ireland during the famine decade, the port of Limerick was a convenient and capable port.

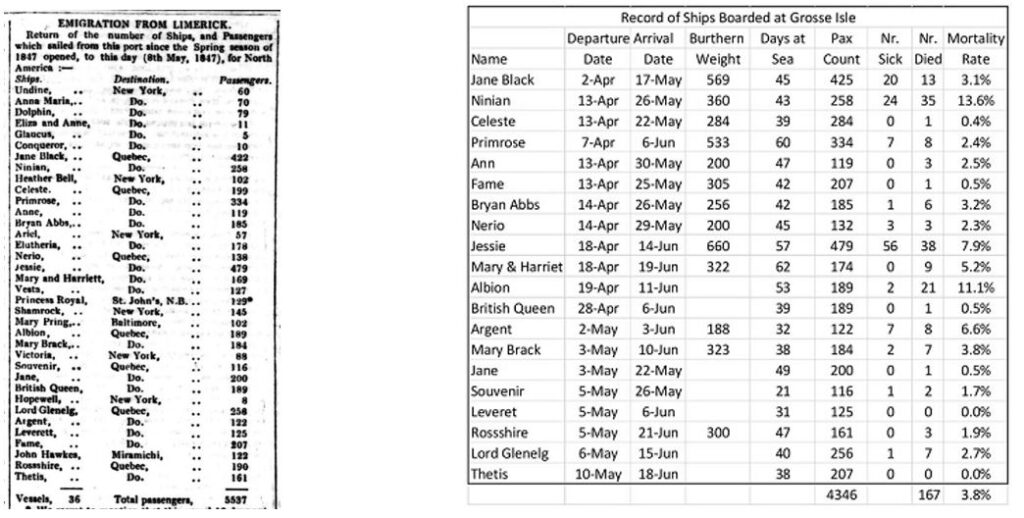

The year 1847, the year the Strokestown emigrants left Roscommon, was the high-water mark of the Famine Exodus to British North America. During the five-month sailing season of 1847, Limerick sent fifty ships to Quebec. Yet despite these numbers, the study of Limerick’s importance has gotten short shrift. The literature is heavy on emigration from Cork, Derry, Dublin and Liverpool. The prevailing story told from these ports is replete with transatlantic passage on so-called coffin ships, contaminated with ship’s fever, burial at sea or burial in unmarked mass graves at the destination. But the prevailing story is not the universal story. Mortality rates differed significantly by port city. Mortality rates of ships sailing from Liverpool in 1847 averaged 30 percent, higher on individual ships, and travel from Cork averaged 20 percent. Whereas travel from Limerick in the sailing season of 1847 averaged about 4 percent, with two ships responsible for skewing the data upwards. Limerick was the safest port from which to emigrate, if on a direct passage to Quebec.

Given the distance back in time, it is difficult to locate authenticated diaries, letters and reliable oral history about a transatlantic emigration experience during the Famine Exodus. But while individual family information may be forever lost, background and context information are recoverable. Resourced with a laptop, access to the internet and nineteenth-century Irish newspapers, I discovered that my family’s experiences in 1847 could be reasonably discerned. I was immediately comforted to learn that passage from Limerick, almost certainly my ancestral family’s departure port, was the healthiest port accessible to them.

The port of Limerick offered several advantages to those within easy travelling distance. It was one of two Irish ports that dominated a direct passage to British North America. The other port was Cork. A direct passage lessened exposure to multiple dangers, such as from predators who aggregated in certain port cities, and contagion. If sailing directly from Limerick to Quebec, the cost was less than passage to the United States. The Limerick port authority was well managed, the emigrating population was demonstrably healthier, and the travel time was, generally, shorter. Departure from any Irish port to Liverpool, there to wait for another ship, was the undoing of many a well-intended emigration scheme.

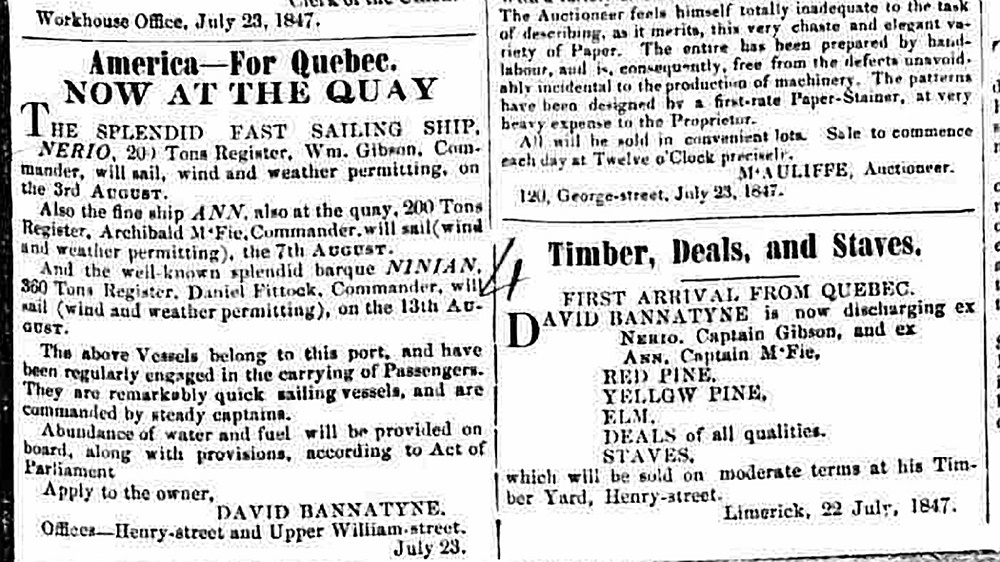

The port of Limerick was able to offer direct passage to British North America because of a long-established timber and dry goods trade. Timber or cargo ships crisscrossed the Atlantic regularly, unloaded their commercial cargo in Limerick, and returned to Canada with human cargo. It was an astute business decision to re-purpose these ships in Limerick with rough, but functional berthing for the return trip carrying determined emigrants. The acceptance of human cargo covered the overhead costs that the ship owner or financers would otherwise expend, and passenger weight served as ballast needed to keep these tall-masted ships navigable on the high seas.

It is an overstatement to say that all timber ships were coffin ships. It was not the structure of the ship that produced ship’s fever, but the condition of the population travelling on those ships. To be sure, these ships were not designed for creature comfort. Their holds were not well ventilated, designed as they were to accommodate bulky commercial cargo that needed to remain dry. When repurposed with communal bunking, the accommodations were Spartan, and there was no privacy. But the ships were not inherently unhealthy, and the crews travelled back and forth on them continually.

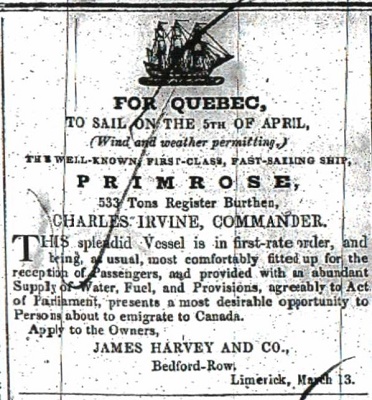

Those considering emigration from the port of Limerick during the Famine Exodus had practical information available to them. The local newspapers carried advertisements giving basic information for all outbound ships. The content was tightly scripted, giving the ship’s name, the name of the captain (often described as a capable mariner), dates of departure, weather permitting, assurances of the availability of communal food and water, as prescribed by the Navigation Acts, and the burthen weight, but not a passenger count. The location of booking agents was also helpfully provided. The agents were distributed in several nearby towns, not just in the port city.

Newspapers carried a Ship’s Intelligence section as well, where one could read about the performance of the advertised ships, the duration of travel to various destinations, and the like. Additionally, newspapers printed articles from those who had already made the passage. These articles often advised prospective emigrants about what to bring, how to pack, and what to expect at a destination. The ships routinely carried back letters from those who had emigrated, sometimes containing remittances to pay the passage for those remaining. We may imagine that the information those letters communicated was widely circulated, directing the decisions of many.

What is not found on the internet, but what may be available in various archives, are captain’s logs, ships’ manifests, and port authority documents. We know when specific ships sailed, but not who was aboard those ships. It seems strange that port authority documents are not available for Limerick, as press accounts spoke highly of Captain Richard Lynch, Royal Navy, Emigration Agent. Captain Lynch was known to board departing ships, to speak with the captain to assure himself that the ship was properly provisioned, to speak with passengers to hear from them about their reception, and to survey the passenger population one last time for disease and the opportunity for contagion. Civic organizations were also involved in assuring appropriate standards were met. These included the press and the trade guilds. The city was justly proud of its reputation as a well-managed port.

There is an adage that a project starting well has a much-improved chance of finishing well. Such appears to be the case of emigration from Limerick in Black ’47, as can be determined by the record keeping of the medical officer at Grosse Isle, the reception and quarantine station located on an island in the St Lawrence River, adjacent to Quebec. Dr George N. Douglas inspected every arriving ship before he would allow its passengers to disembark. Comparing his medical log, found at the Ship’s List website, to the newspaper reporting of ship’s departures from Limerick in the spring sailing of 1847, we are able to determine the mortality rate of individual ships and determine a rough accounting of the port’s mortality rate.

If Dr Douglas determined that the ship’s population was healthy, the immigrants were released to proceed to their final destinations. The cities of Montreal, where my ancestral family went, Ottawa and Toronto, were upstream from Quebec. Today each of these cities is receiving the bronze shoes that are the iconic memorials associated with the Global Irish Famine Way. The port of Limerick was an enabling and capable contributor to the great Famine Exodus. Its historical role in the actualization of the Global Irish Famine Way is deserving of greater investigation.

Ed O’Shaughnessy, a descendant of 1847 County Clare emigrants, is a historian by avocation. He holds an undergraduate degree in history, and graduate degrees in political science and executive management. He has published and presented on the Famine Exodus. One publication, “A Clare family’s famine exodus to Canada”, published in The Other Clare in 2021, is posted at the Clare county library website, history section.