by Ed O’Shaughnessy

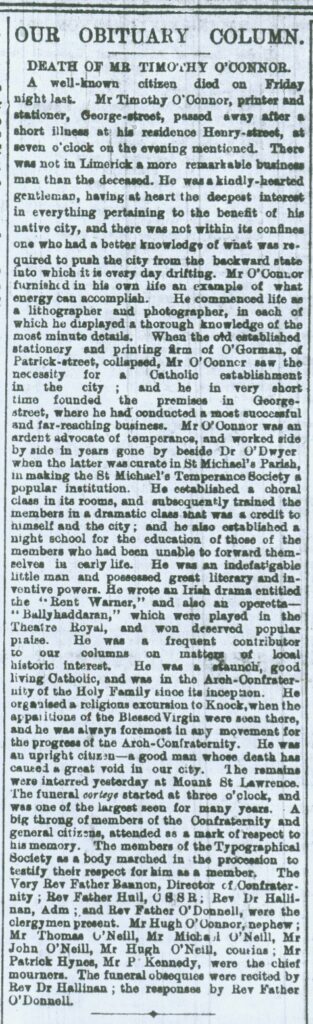

Timothy O’Connor, 1839-1894, was a stationer, printer and photographer with commercial addresses at the corner of George [O’Connell] and Thomas streets and 3 Military Road [O’Connell Avenue], Limerick city. He was man of many interests and accomplishments, and his obituary published in the Limerick Leader in January 1894, makes for an interesting read. ‘A remarkable businessman’ who took ‘the deepest interest in everything pertaining to the benefit of is native city’, he began his working life as a lithographer and photographer, ‘in each of which he displayed a thorough knowledge of the most minute detail.’ He soon established his own business on George Street which was very successful. O’Connor was also a ‘staunch, good living Catholic’ who joined the Arch-Confraternity of the Holy Family at its inception in 1868 and organised a pilgrimage to Knock following the Marian apparitions eleven years later. He subsequently published a book on the subject.[1]

But as fulsome in tribute as that obituary is, no mention is made of Timothy O’Connor’s lasting contribution to Irish History: his photographs of the evictions on the Vandeleur estate, Kilrush, County Clare in July 1888.

Vandeleur Estate Evictions

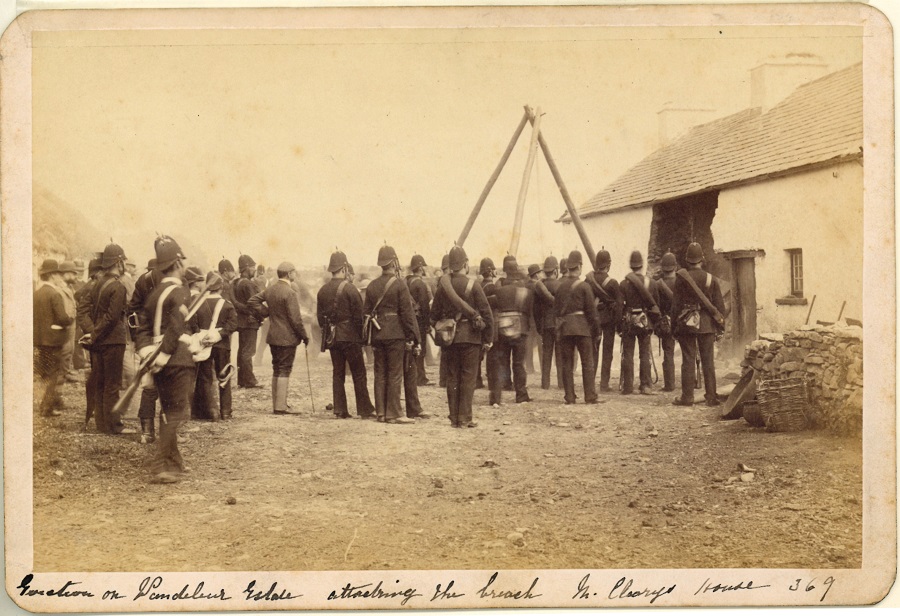

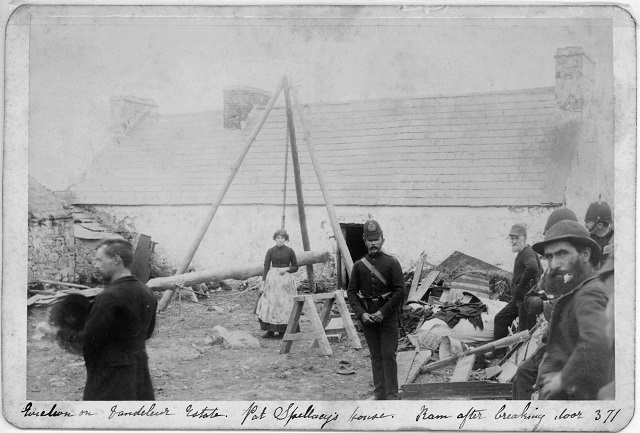

The Vandeleur estate evictions of 1888 stand apart from all other late-nineteeth-century evictions for a number of reasons, not the least because they were so comprehensively photographed. At current estimation some sixty photographs were taken of these evictions, and it was only at these evictions that the iconic battering ram was photographed in use.[2] Why these particular evictions were so uniquely photographed is a question yet to be answered, but the answer is certainly associated with the actions of Timothy O’Connor.

For the purposes of this article, the extant inventory of Vandeleur estate eviction photographs is described as the Lawrence Collection, which includes twenty-one eviction photographs archived at the National Library of Ireland, and, secondly, O’Connor’s inventory of photographs, upwards of twenty-three found in various repositories across countries and continents.[3] Whereas the Lawrence Collection contains a finite number of extant Vandeleur estate eviction photographs, O’Connor’s inventory continues to grow.[4]

O’Connor’s eviction photographs are differentiated from the Lawrence eviction photographs in several regards. The most striking difference between the two inventories is the provenantial notations made by O’Connor on his photographs. Unlike the Lawrence notations, O’Connor’s notations identify by name the Vandeleur tenant families photographed and number his photographs as he took them. These numbers track the sequence of evictions exactly. His schema begins in the low 360s and continues to the 400s.

Another striking difference between the two inventories is their repositories today. The eviction photographs in the Lawrence Collection were likely acquired by the commercially savvy William Lawrence for their commercial value. The acquisition was made known on 11 August 1888 when copies were advertised for sale in the Freeman’s Journal, less than two weeks after the evictions ended on 31 July. Why O’Connor’s eviction photographs were not assembled as a collection is another open question. One answer may be found in the discerning the precipitating motivation for taking the photographs. This author is of the belief that O’Connor was an ardent supporter of the National League, and, as a photographer, possibly offered his talents to support the publicity needs of the Plan of Campaign, as it was employed at the Vandeleur estate evictions.[5]

While we may regret that the precipitating motivation for the creation of these photographs did not lead to a corresponding action to preserve them in a collection, we should take comfort in knowing that many of O’Connor’s photographs are around today because they were recognised as being of importance and value by their original owners. Rather than circulation through commercial channels, O’Connor’s photographs were distributed locally, and often served geopolitical purposes. The author has found O’Connor’s eviction photographs in family collections, in the private papers of Irish Parliamentary Party and English Liberal Party politicians, in collections of observers to the evictions, in library archives, in the collections of collectors, and, from time to time, in auction lots. O’Connor’s eviction photographs are found in Ireland, in the UK, in the US, and are documented as travelling to Australia.

Fortunately it is not too late to preserve O’Connor’s eviction photographs as a collection. The author encourages a collective search for remaining unseen O’Connor eviction photographs. He also supports an initiative to assemble O’Connor’s eviction photographs in a digitized archive. The assembly of the entirety of O’Connor’s eviction photographs in a collection will require negotiations with current owners and custodians for usage permitting. But the goal is a worthy one in search of a sponsoring activity. To that goal the author is willing to collaborate. He will share his spreadsheet accounting of the extant inventory of the Vandeleur estate eviction photographs and the results of his research.

Ed O’Shaughnessy, a descendant of 1847 County Clare emigrants, is a historian by avocation. He holds an undergraduate degree in history, and graduate degrees in political science and executive management. He has published several articles featuring the Vandeleur estate eviction photographs. To find some of these articles visit the Clare County Library website, history section. He has also published and presented on the Famine Exodus. One publication, “A Clare family’s famine exodus to Canada”, published in The Other Clare in 2021, is posted at the Clare county library website, history section. He has previously published an article about the role of Limerick Port during the Famine on this forum.

[1] Limerick Leader, 8 January 1894.

[2] For discussion of the Vandeleur ram see Ed O’Shaughnessy, ‘The Vandeleur ram’. The Other Clare, 43 (2019), pp. 78-83.

[3] This position does not negate the possibility of a third inventory, that of Peter Collins. The existence of a Collins portfolio of Vandeleur estate eviction photographs was documented by the Freeman’s Journal, 13 August 1888, along with the Lawrence collection and O’Connor’s portfolio. But to date, no Collins’ photographs have been found or properly identified as such.

[4] The author has determined that O’Connor took as many as forty photographs, with more than half found or identified. Five of these were found in the year prior to this presentation.

[5] Primary source documentation and the photographs have O’Connor on location before the evictions began, during most days of the eight-day eviction period, and returning to the Vandeleur estate in the weeks following to photograph subsequent actions and eviction sites. O’Connor’s photographs were made available to those who supported the tenants, to those who supported the National League, to those who supported Home Rule, and to selected newspapers.